As a helicopter pilot during the early years (1962-1963) of the Vietnam War, Richard Olsen experienced war almost daily, including being wounded himself by ground fire during a combat assault near Tay Ninh; yet his joy-of-life personality allowed him to see and appreciate the world and people around him and not merely dwell on the battles that raged. When he was there, Vietnam had not been ravaged by war and the bombing and defoliating that came later. To him, even in the midst of war, the moon and sun still rose and set each day, seascapes and landscapes were beautiful, and workers were going about their lives in their fields and villages. His memories and images clearly included the sights and experiences of war, but they also included the lands, villages, cultures, and people.

Later in art school, Olsen was encouraged to use his experiences in Vietnam for content in his art. He assumed that artists painted what they saw: people, places, or events; thus, he translated his experiences into pictures of what he saw, using varying degrees of abstraction and realism. These works included images similar to other wartime art—mainly figural or symbolic works showing the meanness, arbitrariness, horror, harshness, and devastation of war, often with graphic details. However, even though he was producing it, that art did not match his gregarious, energetic, enthusiastic, out-going, and optimistic personality. He had to find other content, or some other way to represent his war memories.

He began using the 602 Club—a local hangout in Madison, Wisconsin—as content for his new paintings. The students, art faculty, and their friends met there each day for rowdy gatherings that often lasted well into the night. He painted what he experienced in the club, using pictorial images, sometimes modelled after famous paintings by other artists, to represent those experiences.

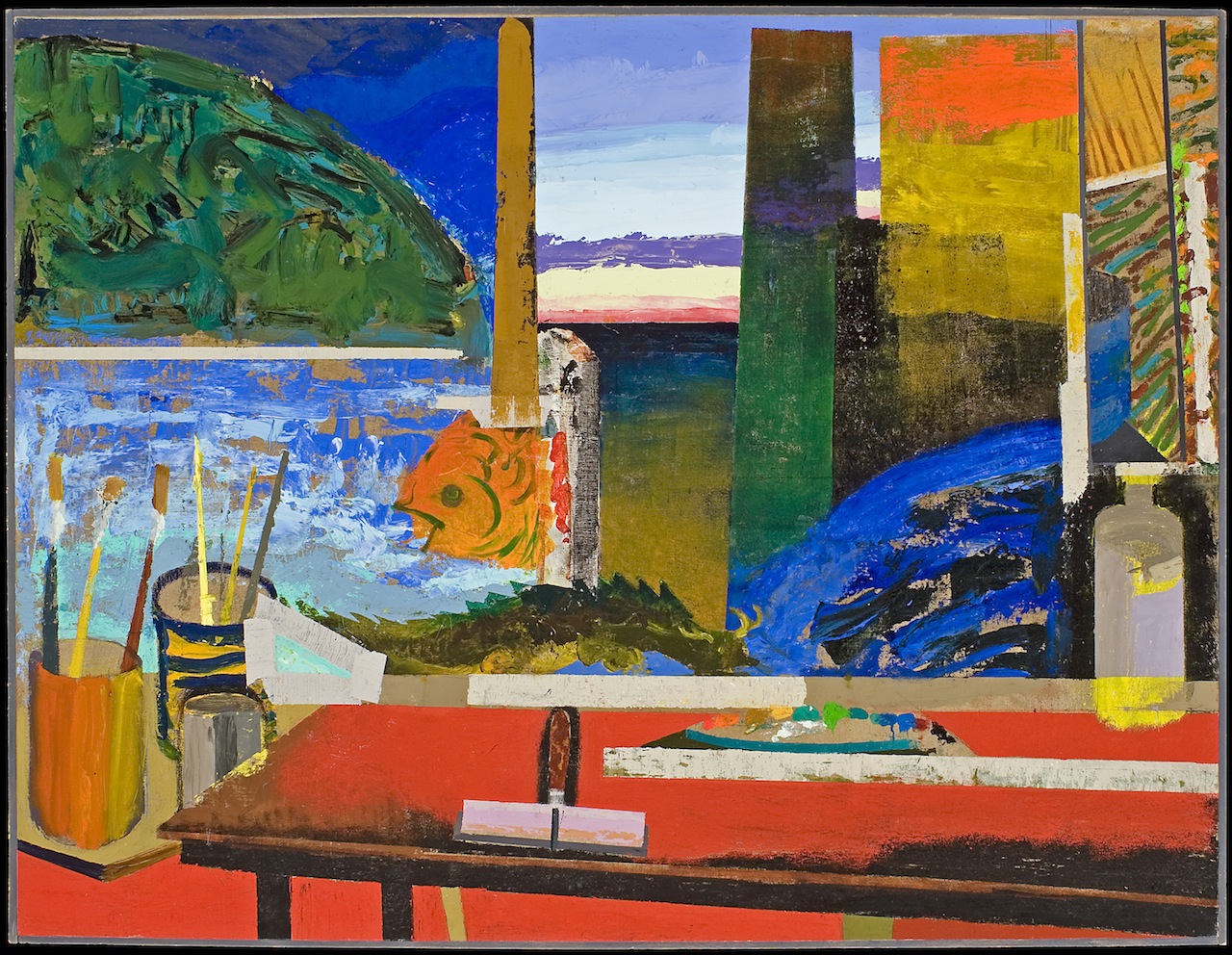

Upon taking his faculty position at the University of Georgia in 1969, Olsen continued his figural and compositional styles from his 602 Club paintings. Yet, his uncertainty about what to paint continued to trouble him. This was a time in universities when the military and the Vietnam War were not comfortable subjects, nor even accepted by his colleagues. Abstraction, with little or no figural content, was the style-of-the-day. While he was not sure what to paint, he was skillful in using his media and materials and in painting both realistic and abstract forms. He decided to rely upon the art cliché, “If you don’t know what to paint, paint your studio wall”. That decision set his artistic direction—he would make paintings of content composed of images and objects inside his studio. It would take 20 years of painting content inside his studio before sources outside his studio were introduced and his mature artistic production began, allowing authentic representation of his Vietnam wartime experiences.

During these intervening years until his mature paintings emerged, Olsen had to learn to make “paintings” of his experiences and not the “pictures” of people, places, objects, or events that he had been making. He knew that his early war images were naked, raw, physical, graphic, and private. He had not been able to communicate his war-related emotions, perspectives, or experiences through them—only pictures of war. Olsen saw that Byron Burford, in his paintings, was able to present someone drenched in valor and misery without using photographic realism. He also remembered that when Jack Kerouac or Ernest Hemmingway wrote about adventures, they were able to get inside of the adventures and describe them so that readers were only remotely aware of the writer as a witness. Olsen wanted to reach that standard in his paintings: to “get inside of his Vietnam adventures and paint them in such a way that viewers comprehended the adventures as experiences while being only remotely aware of the painter”.

To begin the journey, Olsen adopted operating principles: color is what comes off the canvas and not what is put on; distill immediacy; replace passion with time; make flat planes that cover, hide, and keep inside while always being present. Experiences must be objectified, not “subjectified”—the objective rather than subjective frame of reference was essential. He wanted his paintings to show the anguish and other emotional effects while not touching and communicating war itself; covering it up and approaching it from an alternative perspective with more distancing.

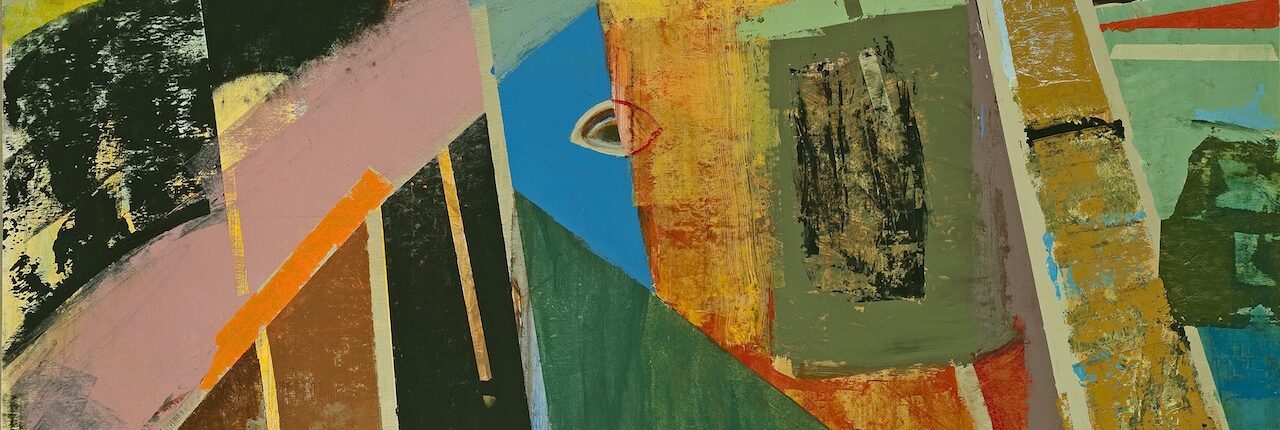

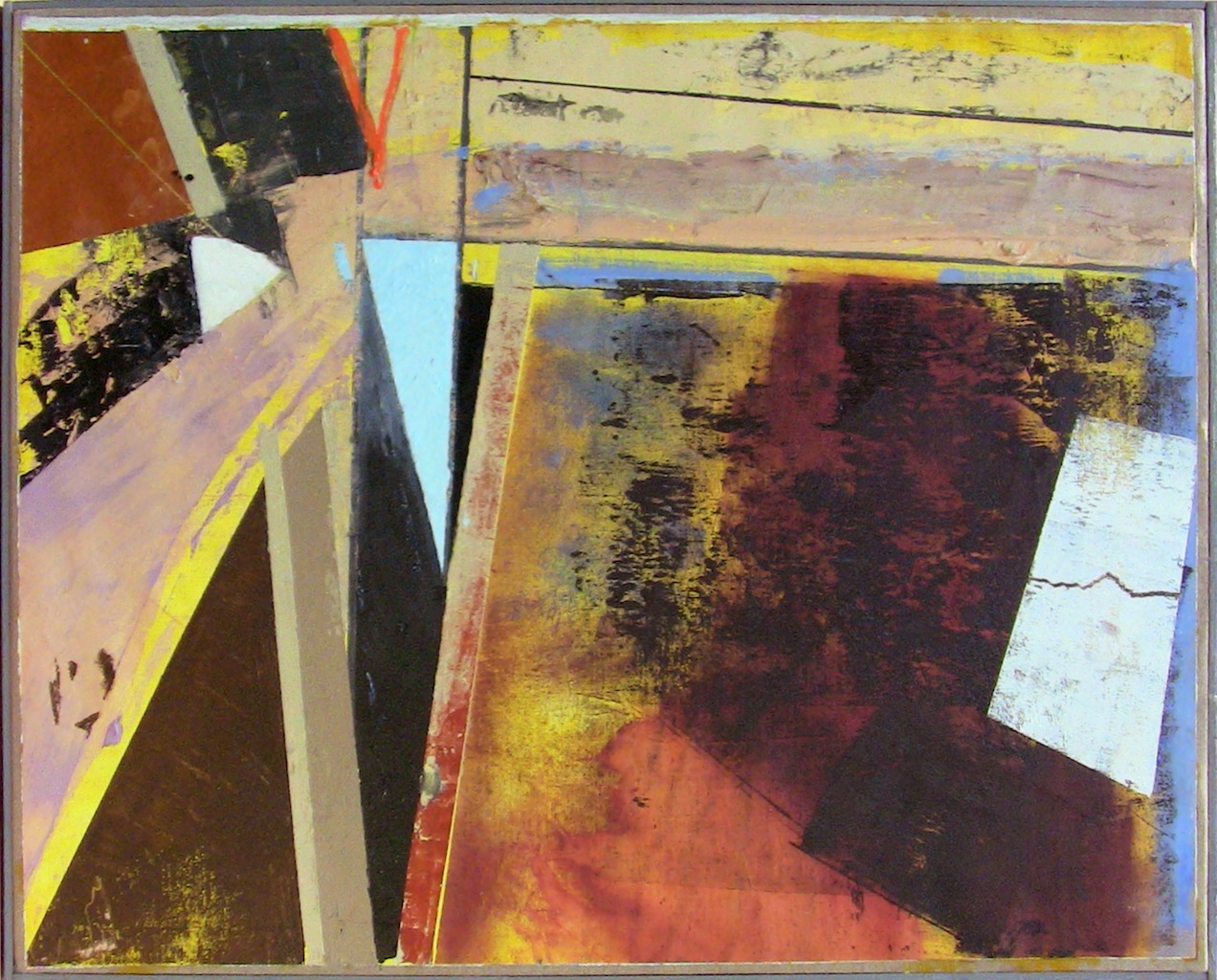

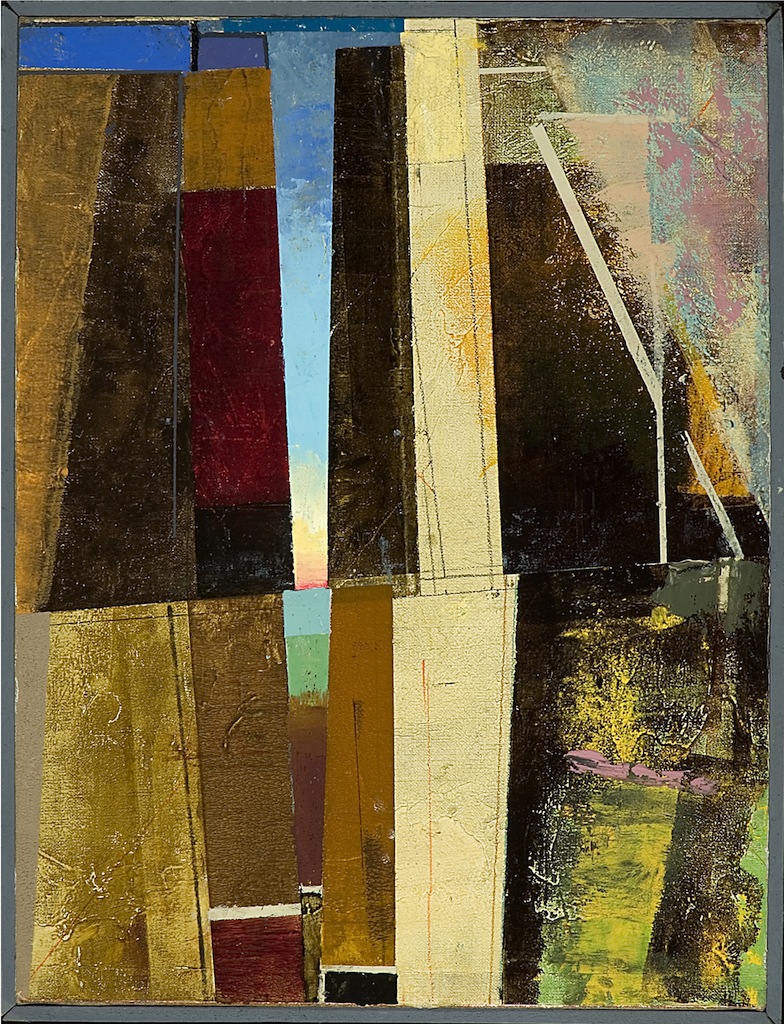

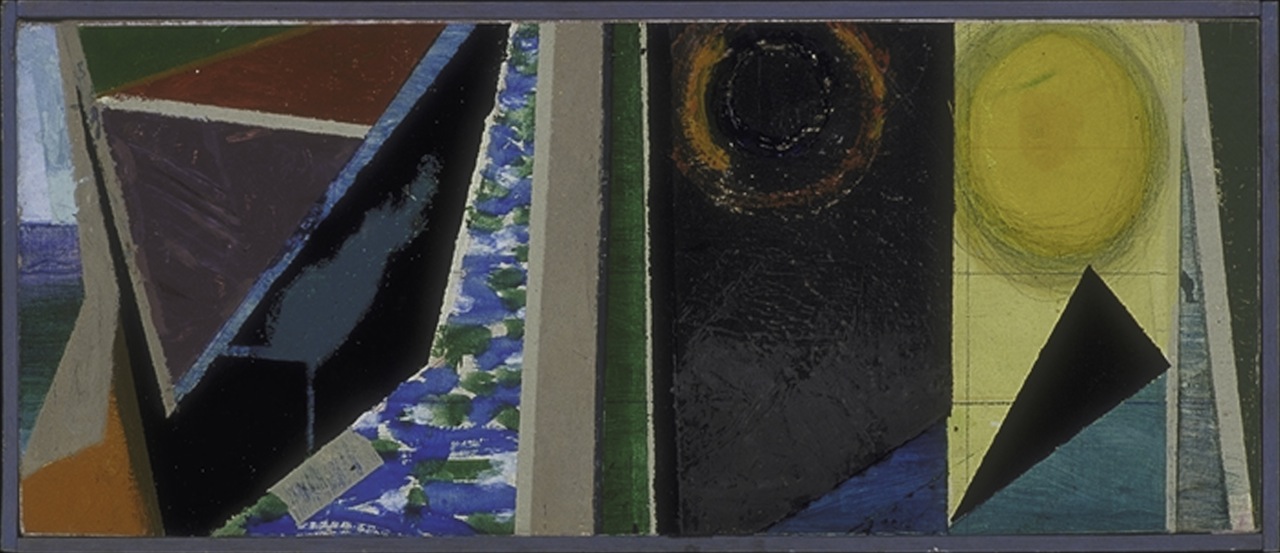

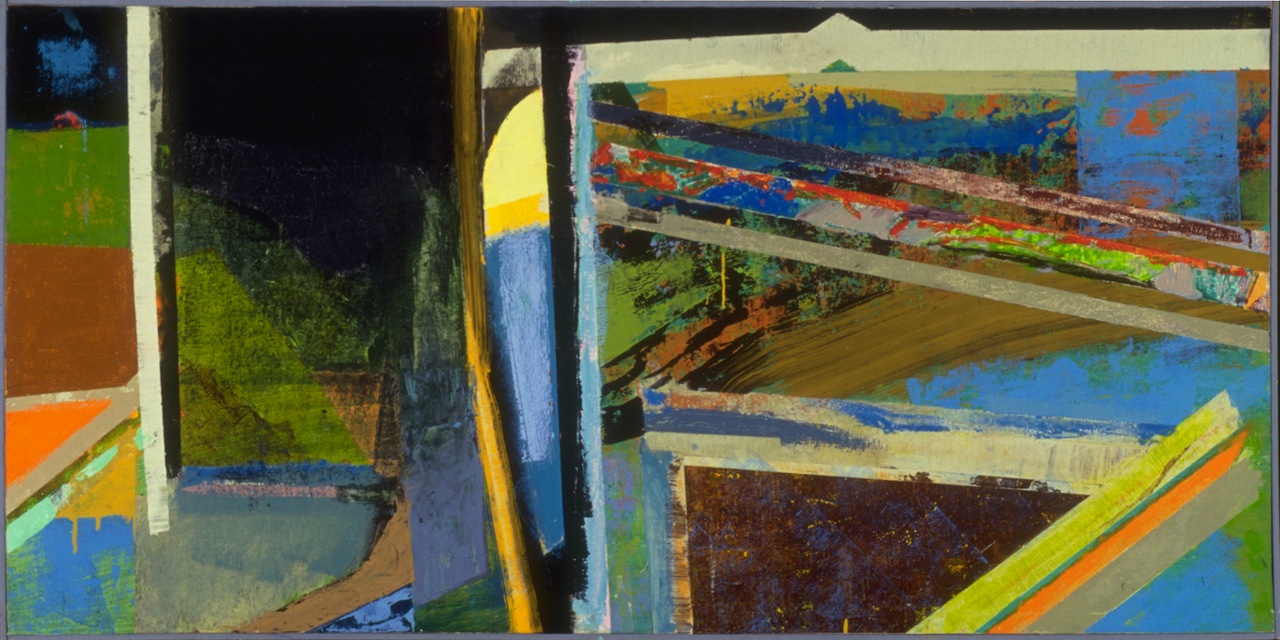

Olsen eventually achieved that standard in his mature Wall paintings, represented in this show. By inventing and adopting a symbolic vocabulary and using those symbols consistently in his work, he was able to compose paintings that expressed war as experiences with all of their actions, horrors, and meaning without using their visual images.

Art Historian Anthony Janson said, “Richard Olsen is the grand master among artists who depict war as their subject. Through his invented and adopted symbols and his mastery of aesthetic principles, he allows viewers to approach the images comfortably, perhaps even while enjoying the aesthetic beauty, until they can recognize and interpret the complex symbols to determine the experience that he is describing. In my judgment, no other artist has developed and adopted a model for describing experience using visual art that matches Olsen’s.” Through Olsen’s paintings, others can know the War through symbols, as it is known by Olsen, who actually was there as a transport helicopter pilot.

To make his paintings, Olsen begins by making a collage, or Calculation, to compose a story (an allegory) that he wants to tell. He pieces together parts cut from photographs from his archives or from new ones made of his ever-increasing collection of paintings and other images and objects on and around his studio. Using a compositional geometry and grid system that he devised, he constructs a design that will guide his painting, much as other artists use studies. While painting, he usually strays from the Calculations to follow inspirations for making the story more vivid, to introduce an image from his memory, or merely to achieve some aesthetic purpose.

Gallery Slideshow:

Loading...

Loading...